|

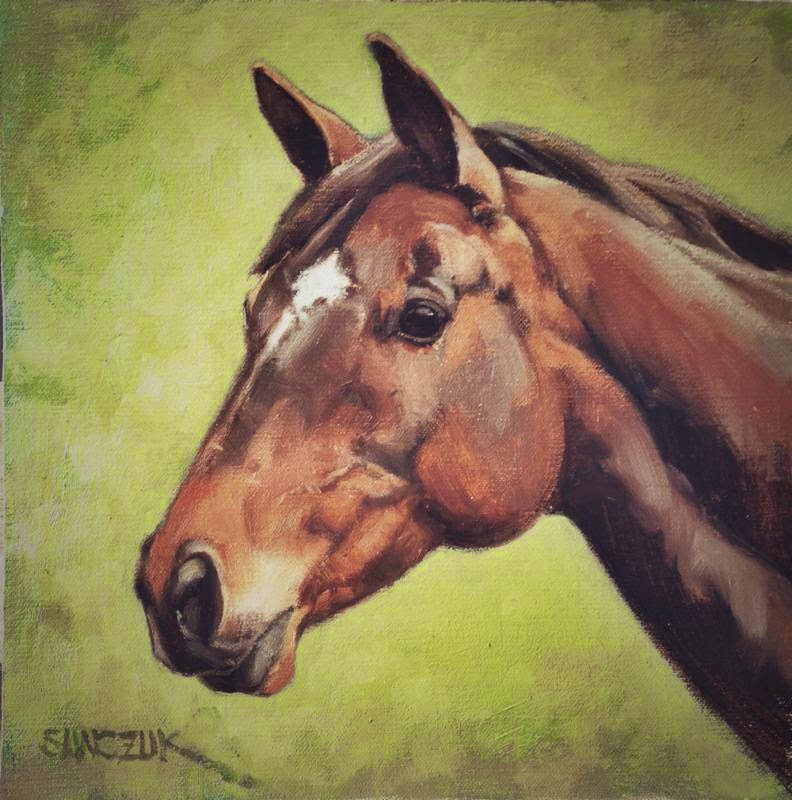

| Enlightened, © oil and cold wax on linen, 24x18 in. |

Think of a moment that is etched in your memory. Perhaps it is a moment from your childhood. Maybe it's something from last week. What is it that you remember about it? Why is that moment recorded in your mind? When I think of childhood memories, I flash back to when I was just two or three years old. I was in bed in the same room with my baby brother. The room was dark, with moonlight streaming in from the window. I could see the baby in his crib, sleeping soundly, when a dragon lifted up out of the small hooked rug on the floor, flew over the crib and out the window. I was sure the dragon had stolen my brother. Of course this was a dream, one that I woke from shrieking in fear, but I remember it from a toddler's perspective, as a completely real experience. I don't remember what the rug looked like, or what color the blankets were, or if there were curtains on the window. What I do remember are the most significant bits that created my experience of that moment.

In our memories, the details become soft around the edges. Sometimes the details even change in our recollections. But the most important essence, the most indispensable information is stored in our neural pathways. In art, that distilled essence is the seed of an idea!

Being primarily a plein air painter, I usually paint what I see or at least an interpretation of it. But sometimes I am gripped by a moment that is too fleeting to capture or too subtle/dark/bright to successfully photograph. Perhaps inclement weather or other responsibilities prevent me from stopping to sketch or paint. In those moments, my only option is to rely on my memory. Trust me - I don't have a photographic memory (or even a moderately good one. I write notes to myself to remember things, and then forget where I left the note)! But my ability to recall the essence of my inspiration improves incrementally the more I do it.

|

| Kealia I, © |

Some years back I participated in a plein air festival in Tucson. A group of us went to Bear Canyon to paint one afternoon. While opening my French easel, I managed to whack the back of my hand into a cactus and came away looking like I'd lost a fight with a porcupine. That was the beginning of my painting session, followed by dropping a pile of pastels on the rocky desert ground, and ending with a downpour (spring monsoon season)! As you might imagine, I was feeling less than confident about my efforts that day. Afterwards, while waiting on our dinner at a local restaurant, my friend Greg McHuron pushed a pen and a napkin across the table towards me. Greg was one of the most knowledgeable and prolific artists I've ever known. "Draw your composition," he said matter-of-factly. I looked at him blankly. "Which composition?" "Draw what you painted today," he explained. So I drew a thumbnail of what I remembered as the composition. "Look!" he said, pointing at the saguaro in front of the mountains that I'd sketched on the napkin. "You've already improved on your idea!" He was right: I had subtly shifted the main elements of my design into a better version of my original composition. Without the distraction of a million compelling details in front of my eyes, that idea became my whole focus.

Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting, John F. Carlson was also a proponent of memory work. "If you train yourself in memory work, you fearlessly attack and rearrange your material, for you can retain your original impression."

Recently, on a family trip to Kaua'i, I witnessed the full moon rising as we drove by Kealia Beach. The moist air and the clouds over the ocean were refracting the moonlight, and the scene was so subtle and glorious I could hardly breathe. I was with my family after a long day of hiking, and even if I'd had the appropriate gear, no one would have had the stamina to wait for me to paint. So I asked my husband to pull over, and we just watched the clouds drifting across the moon, the ocean rolling - trying to absorb the colors in the sky and how the moonlight danced on the waves. It was so lovely, I didn't want it to end. Later in my studio back in Jackson, I could hardly wait to try capturing the moment. I made a drawing, two pastels, and a large oil, just playing with the elements that left the most impression. What fun to relive it.

There are no crutches when working from memory. But often, my memory paintings are the most satisfying to me, because they aren't bogged down by the "reality" of an idea. Freed from unnecessary detail, they are truly about the essence of an idea.

Want to give your memory a little workout? I have a few suggestions to get you started. If you're an artist, start by making a small drawing of the piece on which you most recently worked - no peeking!! What are the main elements? How do they relate to each other? Afterwards, compare it with the original. How has it changed? What did you recall accurately? Next, pay special attention while you're out for a walk or driving somewhere in your car. As soon as you can, get out a sketchbook (or a napkin) and draw what you remember most. Not an artist? You can try it too - just make notes on paper about something you've recently seen or experienced. What caught your eye? What were the sounds, the smells, the light effects that compelled you? Or try explaining it to someone else in a way that they can experience what you saw/smelled/felt/heard. You may find your first few tries somewhat difficult, but if you keep it up, you'll find it easier and easier to capture a moment in your memory. And that is a treat in itself.

Enjoy the memories -

Jen