I

would not suggest that you try to duplicate this encounter because you

may get the non-art-loving variety. It's hard to tell the difference.

Moose

on the other hand, do not care if you are an artist or typical

tourist... keep your distance! Though I've seen moose many times while

out painting, my most unnerving encounter came during one of my

earliest forays into Teton Park soon after my family moved here. I was

painting just South and East of the Moose bridge over the Snake river

trying to capture a likeness of the Tetons and totally absorbed in this

effort. Suddenly, a large, dark shape appeared on the bench below me

accompanied by a bellow. My first reaction was... BEAR! I played some

basketball as a youngster and though never a great leaper, I did a 36"

vertical that day. I should have had a selfie to satisfy the doubters

out there (my flip phone doesn't take selfies).

Deer

and pronghorns are often just curious and will move in for a closer

look. The autumn seems to bring smaller animals and birds in closer

since they throw caution to the wind in their search for food before the

harsh winter sets in. I was painting Teewinot near the pasture

adjacent to the Taggart lake area when a wren landed on my backpack. He

next hopped over to my palette and then settled on my hand as I was

preparing to lay down a stroke. What caused this? Did he not like the

color? I put it on anyway. The magpies are the bravest and most comical

of spectators. They often will perch next to you and carry on a

one-sided magpie conversation with a steady stream of gibberish. It is

hard to tell what they really think of the work, but they do hang

around for a longer time than most of my visitors. One little guy that

you may be lucky to see will be a weasel (a.k.a., ermine, if winter).

They will pop up in log or brush piles, stare at you with that Alfred

E. Newman face, disappear and the reappear in seconds about 25 feet

away. They are fast! Be forewarned! Cranes don't care for company at

any time. You might be 200 yards away from them and they will put on a

constant stream of noise until you move. I don't paint near cranes any

more.

You

might be thinking that I haven't mentioned bear encounters. Here it

goes. I was painting near the Lucas/Fabian cabins on a beautiful summer

day and had made a pretty fair effort. The afternoon light was

changing, so I packed up and started back to my old Wagoneer. I carry my

French easel on an old hunt pack frame and when I walk, the brushes

rattle in the metal pans so much that I sound like an old Yankee

peddler. I was near my car, when suddenly there were two splashes in

Cottonwood creek next to me. A grizzly sow and cub had just plunged in

about 25 feet ahead of me. My noise-making made them aware of my

presence, and they ignored me. I, of course, was not that calm as I

slowly backed away and stood behind a power pole. The bears would not

move away from the vicinity of my Jeep, and I had to take a wading

detour across Cottonwood creek in cowboy boots. The next morning, I

bought bear spray.

I

hope that you are somewhat enlightened about the wildlife encounter

possibilities. Some of these things may have happened to you. Use

caution and enjoy your blessings when you are fortunate enough to mingle

with these wonderful creatures along the paintbrush trail.

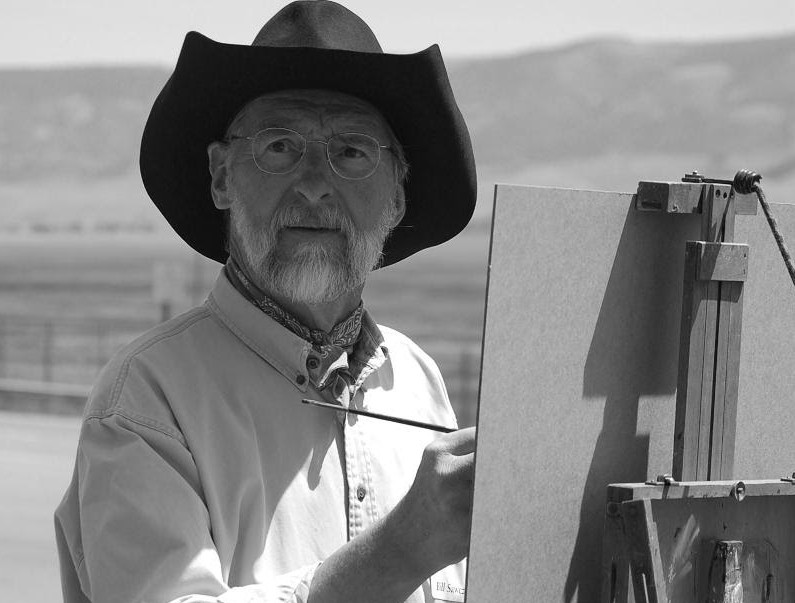

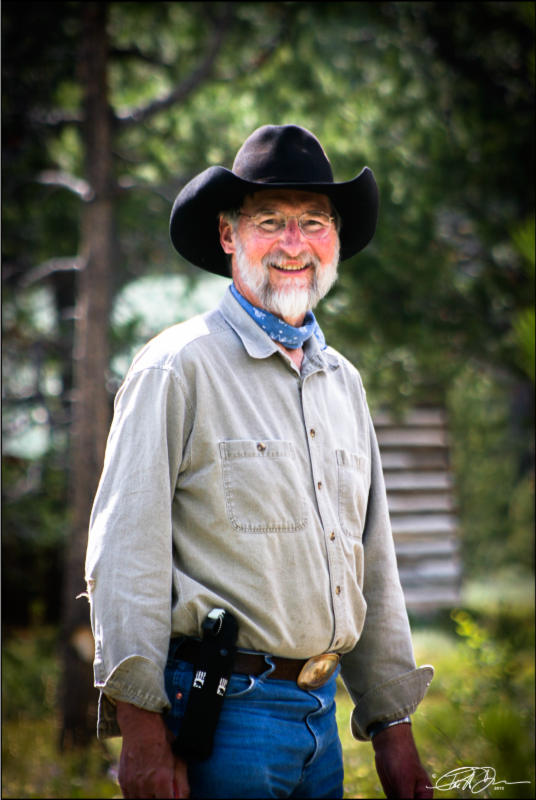

Behind the Brushes

"Along the Paintbrush Trail"

Bill Sawczuk

|

This blog is a forum for discussing the thought process and the artistic process of artists Kathryn Mapes Turner, Bill Sawczuk, and Jennifer L. Hoffman. We want to share the joy of art with you - one little post at a time.

Wednesday, September 28, 2016

Along the Paintbrush Trail

Sunday, August 28, 2016

Art is at the Heart of our National Parks

Plein

air painting is and has been an important part of the life and work of

the artists of Trio Fine Art. And much of this painting practice takes

place at the foot and in the heart of the mountains surrounding Grand

Teton National Park.

As

I'm sure you all know, this month marks the 100th anniversary of the

National Parks Service (NPS), and as such, the 100th anniversary of our

beautiful Grand Teton National Park. Art and the NPS go hand in hand;

early explorers to the area, particularly Thomas Moran of the Hayden

Geological Survey of 1871, incorporated sketch and painting into their

study of the land. "The story of Thomas Moran's paintings and

Henry Jackson's photography really showcases the impact of art. It was

their images that convinced Congress to set aside Yellowstone as a park,

" says Kathryn Turner. "Art is a powerful medium - whether photography,

film, or fine art. It touches us at a deep, emotional level, and this

stays with us."

|

"Wetlands" 16 x 20 oil on canvas by Kathryn Mapes Turner. Found on page 192 of

Painters of Grand Teton National Park.

|

|

"Hoback Junction Blues" 8 x 10 oil on board by Jennifer Hoffman.

Found on page 175 of

Painters of Grand Teton National Park.

|

"When

painting outdoors, we have to endure challenging light, wind, heat,

cold, sudden storms, driving rain, sleet, snow, hail, sunburn, and all

manner of insects - often all in one day!... But one of the things I

love about painting is that when I'm out in the field, basically

standing in one place for a few hours, I become part of the environment

to the creatures who live there... At the end of the day, sometimes the

paintings work and sometimes they don't, but the experience and the

inspiration is beyond compare."

|

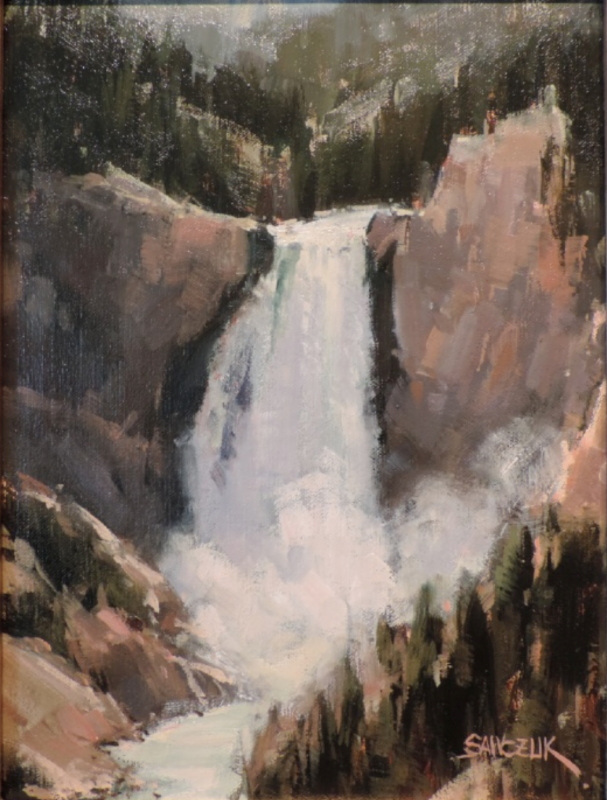

"Red Roofs of the Bar BC" 16 x 20 oil on linen by Bill Sawczuk. Found on page 148 of

Painters of Grand Teton National Park.

|

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Painting the Park. Happy 100th birthday to National Park Service!

|

| "Never Tired" 12 x 36 oil on canvas by Kathryn Turner |

|

Kathryn painting en plein air in Grand Teton National Park

Photographer: Latham Jenkins (@lathamJenkins)

|

The 90th anniversary of the ranch coincides with the 100th

Anniversary of the National Park System. This enactment of the US

Congress, to set aside land for the benefit and enjoyment of the

American people, was a novel idea. Because of it we have Yosemite, Mount

Rainier, Mesa Verde, and Rocky Mountain National Park.

|

| "Thermal Spectrum" 11 x 14 (detail) by Jennifer Hoffman |

“I love how vast and subtle our parks are. I know Grand

Teton and Yellowstone best, but even in Arches or the Badlands, Point

Reyes or the Everglades, the magic is in looking beyond the obvious. My

friend Kerry Butler had a chance to visit Grand Teton [National Park]

and Yellowstone National Park recently. He told me, ‘...the real magic

is in the the little things. The things that only you and your traveling

partners might get to witness. I wish every day that I had the

time/opportunity to be there more often; pull over to the side of the

road, get out and see what happens if I just hang around for a little

while.’ That is what our national parks offer us. That is exactly what I

love sharing through my artwork.

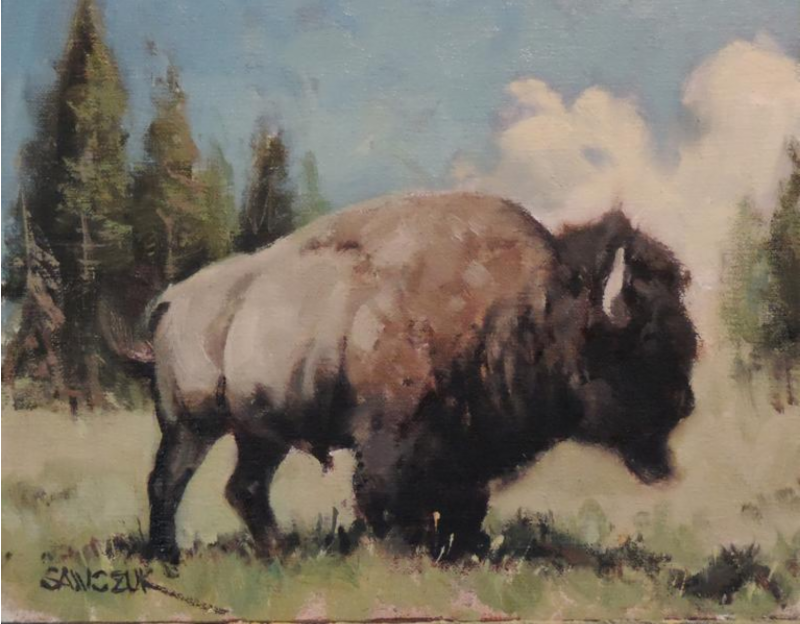

Bill Sawczuk’s introduction to the National Parks came in 1972

during a motorcycle trip around the country. He eventually ended up in

Yellowstone, and was overwhelmed by its size and wildness. He and his

wife now pay a visit there every couple weeks. His favorite area is

Lamar Valley and the Northeast corner.

I love knowing that these lands are preserved so that my

daughter and future generations will be able to have the same experience

of wildness and beauty that I enjoy.”

- Jennifer Hoffman

|

| "In the West" 12 x 12 oil on linen by Bill Sawczuk |

“In these open, wild spaces I can imagine the past. Where

the indigenous people would hunt and fish, or the Hayden expedition

explored.”

July 6th, 2016, Bill will kick off the solo exhibition schedule at Trio Fine Art, featuring his latest body of work. This collection, entitled "A Closer Look," refers to how through art we can experience a deeper reflection of the natural world. In these paintings, Bill strives to pay a tribute to it by revisiting familiar subjects in a new way.

Find all three of our work featured in Donna and James Poulton's newly released book, Painters of Grand Teton National Park. A collection of nearly

Visit the National Museum of Wildlife Art this summer to view our artwork that is included in the Grand Teton Park in Art exhibition. For more information, here's an article on this exhibit and the special installation featuring a plein air time-lapse from my favorite painting spot.

Lastly, we hope you will join us for our summer exhibitions at Trio Fine Art, as well the much-loved Plein Air for the Parks Show and Benefit Sale at the Craig Thomas Discovery Center, July 13th - July 17th, 2016. Trio will join some of the top landscape painters to celebrate the majestic beauty of Grand Teton National Park with paint and canvas.

Kathryn Mapes Turner

On most other days, one can find Bill in our own Grand Teton

National Park painting plein air where he is always encountering the

diversity of the landscape depending on the time of day or season.

“Each day we go out to paint and look for something, but don’t

always know what we are looking for. When we are struck by a scene that

stirs us emotionally, we have found our subject. Then we have to be

selective because we can’t paint it all. We must paint what is essential

to communicate this feeling.” - Bill Sawczuk

July 6th, 2016, Bill will kick off the solo exhibition schedule at Trio Fine Art, featuring his latest body of work. This collection, entitled "A Closer Look," refers to how through art we can experience a deeper reflection of the natural world. In these paintings, Bill strives to pay a tribute to it by revisiting familiar subjects in a new way.

The Parks and Inspiration

The National Park Service mission is to preserve the natural

and cultural resources and values of the

National Park System for the

enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.

This year marks a celebration of the past, and excitement for the

future. David Veja, Grand Teton National Park superintendent says “Let’s

take time to celebrate our accomplishments and the significant

contributions that have been made over the past 100 years. More

importantly, let’s embrace the opportunity to inspire a new generation

of park enthusiasts and stewards.” We at Trio believe artwork can play a

special role in this mission. Through our art, we hope to help others

make meaningful connections of their own to our beautiful world around

them, leading to a second century of stewardship and care for the

natural world.

“I love feeling a part of the artistic history of

land preservation. Artists were integral in igniting the public’s

imagination - they encouraged the conversations and created a sense of

wonder and intrinsic value in our wild lands that ultimately led to the

conservation of our parks. I am honored to be a small but passionate

part of that legacy."

- Jennifer Hoffman

- Jennifer Hoffman

four

hundred paintings, drawings, and photographs, from Thomas Moran to

Edward Hopper, this book is a survey of the long history of artists'

interpretations of the Teton Range and Jackson Hole area.

Visit the National Museum of Wildlife Art this summer to view our artwork that is included in the Grand Teton Park in Art exhibition. For more information, here's an article on this exhibit and the special installation featuring a plein air time-lapse from my favorite painting spot.

Lastly, we hope you will join us for our summer exhibitions at Trio Fine Art, as well the much-loved Plein Air for the Parks Show and Benefit Sale at the Craig Thomas Discovery Center, July 13th - July 17th, 2016. Trio will join some of the top landscape painters to celebrate the majestic beauty of Grand Teton National Park with paint and canvas.

Kathryn Mapes Turner

"Painting the Park. Happy 100th birthday to National Park Service!"

Behind the Brushes

www.TrioFineArt.com

Monday, May 30, 2016

My Passion for Pastel

Over the years, I’ve dabbled in all sorts of media: pencil, charcoal, silverpoint, watercolor, gouache, oil, etching, monotype, serigraph, acrylic… you name it, I’ve tried it. When I began to take plein air painting seriously, I started working in oils almost exclusively. It takes a lot of effort to become even slightly adept at painting outdoors. It made sense to focus on one medium and get comfortable using it.

|

Jennifer L. Hoffman, Lyric, pastel on

paper, c. 2005.

|

Despite that conviction, after looking at some Degas pastel sketches at the Denver Art Museum, I’d bought a box of 30 pastel half-sticks on sale at an art supply store. I didn’t have a specific plan for using them, but after they sat on the shelf in my studio for a while, they began to catch my eye. I felt an increasing itch to try them out. Just for fun. Though it’s been over 10 years, the day I finally gave into that urge is surprisingly clear in my mind. It was spring, and I went outside to cut serviceberry blossoms and mountain bluebells. I put a few sprigs into a small green jar, set them on a white tablecloth, and pulled the untouched box of pastels off the shelf. Not having an ideal place to set up for pastels, I pulled out a piece of gray Canson paper and a drawing board, sat cross-legged on the floor, and started working. I recall being instantly engrossed in the process. Time simultaneously stood still and passed in the blink of an eye. It was a bit like falling in love. I knew from the moment I finished that still life that I would never stop using pastels.

Since I was a child, I have loved to draw. Most exciting for me, when I first dragged a pastel across that sheet of paper, were the similarities to both drawing and painting. My hand was in contact with the surface of the paper. The pastel stick responded to even the slightest pressure changes. I could make lines and gestural marks. There was no drying time – no waiting to apply the next layer. But I could also quickly cover large swaths of paper with masses of color. The color was opaque. I could layer colors to create new ones, create texture, build impasto. I could blend or not blend.

|

Details of color layering and blending with pastels.

|

|

| Jen using pastels in the field. |

And because there is no time-consuming color mixing involved, I love to use pastels in the field. As a plein

air enthusiast, I often am painting in quickly changing conditions.

Being able to figure out my composition and get straight to work

allows me to react more immediately to the experience. It also allows

me to grab a thought, a feeling, a fleeting moment of light in just a

few minutes – to record it on paper and in my mind so that I can access

it later. Pastels are the perfect medium for me to record a visual

memory.

|

Jennifer L. Hoffman, Thermal Spectrum, pastel on mounted

paper, 11x14 in., 2016.

|

|

Mary Cassatt (1844 –1926), The Pink Sash

(Ellen Mary Cassatt), c. 1898, Pastel on paper, 24 x 19 ¾ in

|

|

Jennifer L. Hoffman, Gradient, pastel on mounted paper,

10x6 in., 2016.

|

But most of all, pastel has helped me access something deeper and more personal. By using the most ephemeral of media - sticks of colorful dust - to create a lasting image, I make a fragile, enduring mark. In that way, pastel is a bit like magic, a bit like music, a bit like poetry, and a lot like us.

Behind the Brushes

"My Passion for Pastel"

Trio Fine Art

Thursday, April 28, 2016

The pleine air painting and a question from Pope Julius II

Is it finished?

The story is told that when Michelangelo was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Pope Julius II would look up and shout to him "When will you be done?," and Michelangelo would shout back "When it is finished!" Of course they were talking about physically finishing the paintings of the entire ceiling and not just one particular segment. This, admittedly is a round about way of taking us to pleine air painting and the question of when it is finished. Pleine air painting poses a very different question of when a work is finished versus a studio painting, of course, because of time constraints. One could argue that this statement is not true, as finished means finished no matter where the painting takes place. I will be truthful and tell you that most of my paintings are not alla prima and require some work in the studio to be "presentable." Occasionally, I come upon a scene that is so perfect for pleine air work that I can figuratively paint it before I paint it. These paintings do not need a single stroke after the work out of doors. For me, this is rare but it does happen.

The question is, "How do you know when

the painting is complete?" The answer lies in another question, "Does

your picture represent all that you wished to say of the scene before

you?" We know that something can always be added to a painting to

"finish" it. We think that we need more detail, some color correction,

maybe some composition rearrangement, more design elements, softening

of edges, nicer brushstrokes, and so forth. It is at this point that we

should lay the brushes down and take a closer look at the painting. What do I mean by a closer look? Analyze the scene before you and

revisit your inspiration for choosing it to paint. What was it that

made you want to express your feelings in the painting? Was it the mood

or the particular subject or the raw emotion? How could you best capture these feelings in paint? Do you still see these emotions in your

painting up to this point? Does something else need to be added to

express your emotion more fully? I speak for myself when I say that I

have ruined many pleine air paintings by answering these questions

incorrectly. Sometimes the rather rough appearance of a two-hour painting

worries me. I think that I must do more in spite of the fact that I

like what I have done, and I feel that it tells the story. Why do I

question the completeness of my work when I am satisfied with the

result? Is it because I fear it won't sell or others might say that it seems "unfinished?"

I enjoy painting in the vignette style, which leaves some of the canvas unpainted. I have left it that way because, simply, there was no more to say. I don't know at the start of the picture that it will be a vignette because I haven't concentrated on making the whole canvas a picture. I am working at using the space I need to paint the subject. This is a fault of mine, so I shouldn't be sensitive to comments about completing the picture (*expletives deleted*). Many paintings can be touched up in the studio... but, be careful! This is where the painting is most susceptible to be ruined. Stand back 4 feet and keep your brush off of the painting until you know exactly what you will do to improve it. If you don't really know what to do, leave it alone! You have then made the best decision.

What we have talked about here is one of the most difficult of questions that an artist asks himself. If you have a good, solid feeling for what you are trying to say, then you WILL know when you have said it. A lukewarm response to the subject before you will almost always result in a lukewarm representation in paint. So, happy painting and remember Pope Julius!

The story is told that when Michelangelo was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Pope Julius II would look up and shout to him "When will you be done?," and Michelangelo would shout back "When it is finished!" Of course they were talking about physically finishing the paintings of the entire ceiling and not just one particular segment. This, admittedly is a round about way of taking us to pleine air painting and the question of when it is finished. Pleine air painting poses a very different question of when a work is finished versus a studio painting, of course, because of time constraints. One could argue that this statement is not true, as finished means finished no matter where the painting takes place. I will be truthful and tell you that most of my paintings are not alla prima and require some work in the studio to be "presentable." Occasionally, I come upon a scene that is so perfect for pleine air work that I can figuratively paint it before I paint it. These paintings do not need a single stroke after the work out of doors. For me, this is rare but it does happen.

|

| This is an alla prima piece measuring 20 x 16 |

I enjoy painting in the vignette style, which leaves some of the canvas unpainted. I have left it that way because, simply, there was no more to say. I don't know at the start of the picture that it will be a vignette because I haven't concentrated on making the whole canvas a picture. I am working at using the space I need to paint the subject. This is a fault of mine, so I shouldn't be sensitive to comments about completing the picture (*expletives deleted*). Many paintings can be touched up in the studio... but, be careful! This is where the painting is most susceptible to be ruined. Stand back 4 feet and keep your brush off of the painting until you know exactly what you will do to improve it. If you don't really know what to do, leave it alone! You have then made the best decision.

What we have talked about here is one of the most difficult of questions that an artist asks himself. If you have a good, solid feeling for what you are trying to say, then you WILL know when you have said it. A lukewarm response to the subject before you will almost always result in a lukewarm representation in paint. So, happy painting and remember Pope Julius!

Behind the Brushes

"The pleine aire painting and a question from Pope Julius II"

Trio Fine Art

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)