|

| "Never Tired" 12 x 36 oil on canvas by Kathryn Turner |

|

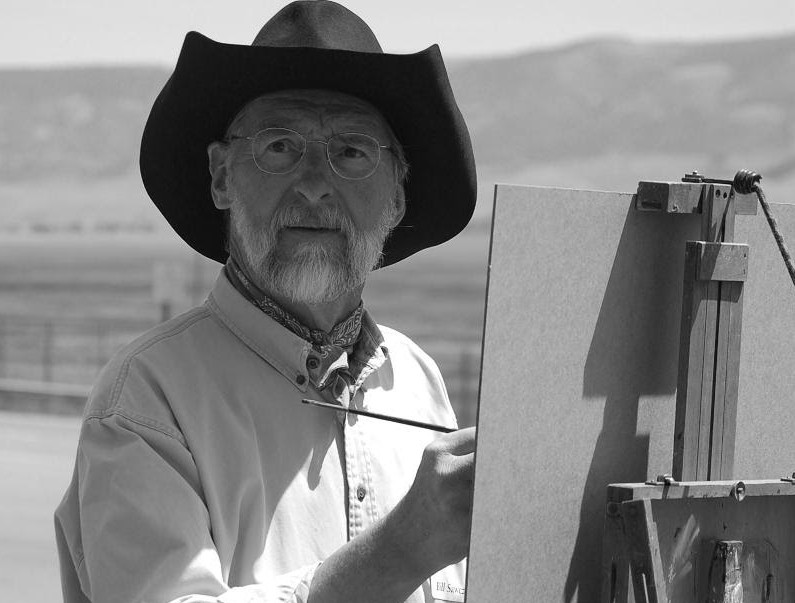

Kathryn painting en plein air in Grand Teton National Park

Photographer: Latham Jenkins (@lathamJenkins)

|

The 90th anniversary of the ranch coincides with the 100th

Anniversary of the National Park System. This enactment of the US

Congress, to set aside land for the benefit and enjoyment of the

American people, was a novel idea. Because of it we have Yosemite, Mount

Rainier, Mesa Verde, and Rocky Mountain National Park.

|

| "Thermal Spectrum" 11 x 14 (detail) by Jennifer Hoffman |

“I love how vast and subtle our parks are. I know Grand

Teton and Yellowstone best, but even in Arches or the Badlands, Point

Reyes or the Everglades, the magic is in looking beyond the obvious. My

friend Kerry Butler had a chance to visit Grand Teton [National Park]

and Yellowstone National Park recently. He told me, ‘...the real magic

is in the the little things. The things that only you and your traveling

partners might get to witness. I wish every day that I had the

time/opportunity to be there more often; pull over to the side of the

road, get out and see what happens if I just hang around for a little

while.’ That is what our national parks offer us. That is exactly what I

love sharing through my artwork.

Bill Sawczuk’s introduction to the National Parks came in 1972

during a motorcycle trip around the country. He eventually ended up in

Yellowstone, and was overwhelmed by its size and wildness. He and his

wife now pay a visit there every couple weeks. His favorite area is

Lamar Valley and the Northeast corner.

I love knowing that these lands are preserved so that my

daughter and future generations will be able to have the same experience

of wildness and beauty that I enjoy.”

- Jennifer Hoffman

|

| "In the West" 12 x 12 oil on linen by Bill Sawczuk |

“In these open, wild spaces I can imagine the past. Where

the indigenous people would hunt and fish, or the Hayden expedition

explored.”

July 6th, 2016, Bill will kick off the solo exhibition schedule at Trio Fine Art, featuring his latest body of work. This collection, entitled "A Closer Look," refers to how through art we can experience a deeper reflection of the natural world. In these paintings, Bill strives to pay a tribute to it by revisiting familiar subjects in a new way.

Find all three of our work featured in Donna and James Poulton's newly released book, Painters of Grand Teton National Park. A collection of nearly

Visit the National Museum of Wildlife Art this summer to view our artwork that is included in the Grand Teton Park in Art exhibition. For more information, here's an article on this exhibit and the special installation featuring a plein air time-lapse from my favorite painting spot.

Lastly, we hope you will join us for our summer exhibitions at Trio Fine Art, as well the much-loved Plein Air for the Parks Show and Benefit Sale at the Craig Thomas Discovery Center, July 13th - July 17th, 2016. Trio will join some of the top landscape painters to celebrate the majestic beauty of Grand Teton National Park with paint and canvas.

Kathryn Mapes Turner

On most other days, one can find Bill in our own Grand Teton

National Park painting plein air where he is always encountering the

diversity of the landscape depending on the time of day or season.

“Each day we go out to paint and look for something, but don’t

always know what we are looking for. When we are struck by a scene that

stirs us emotionally, we have found our subject. Then we have to be

selective because we can’t paint it all. We must paint what is essential

to communicate this feeling.” - Bill Sawczuk

July 6th, 2016, Bill will kick off the solo exhibition schedule at Trio Fine Art, featuring his latest body of work. This collection, entitled "A Closer Look," refers to how through art we can experience a deeper reflection of the natural world. In these paintings, Bill strives to pay a tribute to it by revisiting familiar subjects in a new way.

The Parks and Inspiration

The National Park Service mission is to preserve the natural

and cultural resources and values of the

National Park System for the

enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.

This year marks a celebration of the past, and excitement for the

future. David Veja, Grand Teton National Park superintendent says “Let’s

take time to celebrate our accomplishments and the significant

contributions that have been made over the past 100 years. More

importantly, let’s embrace the opportunity to inspire a new generation

of park enthusiasts and stewards.” We at Trio believe artwork can play a

special role in this mission. Through our art, we hope to help others

make meaningful connections of their own to our beautiful world around

them, leading to a second century of stewardship and care for the

natural world.

“I love feeling a part of the artistic history of

land preservation. Artists were integral in igniting the public’s

imagination - they encouraged the conversations and created a sense of

wonder and intrinsic value in our wild lands that ultimately led to the

conservation of our parks. I am honored to be a small but passionate

part of that legacy."

- Jennifer Hoffman

- Jennifer Hoffman

four

hundred paintings, drawings, and photographs, from Thomas Moran to

Edward Hopper, this book is a survey of the long history of artists'

interpretations of the Teton Range and Jackson Hole area.

Visit the National Museum of Wildlife Art this summer to view our artwork that is included in the Grand Teton Park in Art exhibition. For more information, here's an article on this exhibit and the special installation featuring a plein air time-lapse from my favorite painting spot.

Lastly, we hope you will join us for our summer exhibitions at Trio Fine Art, as well the much-loved Plein Air for the Parks Show and Benefit Sale at the Craig Thomas Discovery Center, July 13th - July 17th, 2016. Trio will join some of the top landscape painters to celebrate the majestic beauty of Grand Teton National Park with paint and canvas.

Kathryn Mapes Turner

"Painting the Park. Happy 100th birthday to National Park Service!"

Behind the Brushes

www.TrioFineArt.com